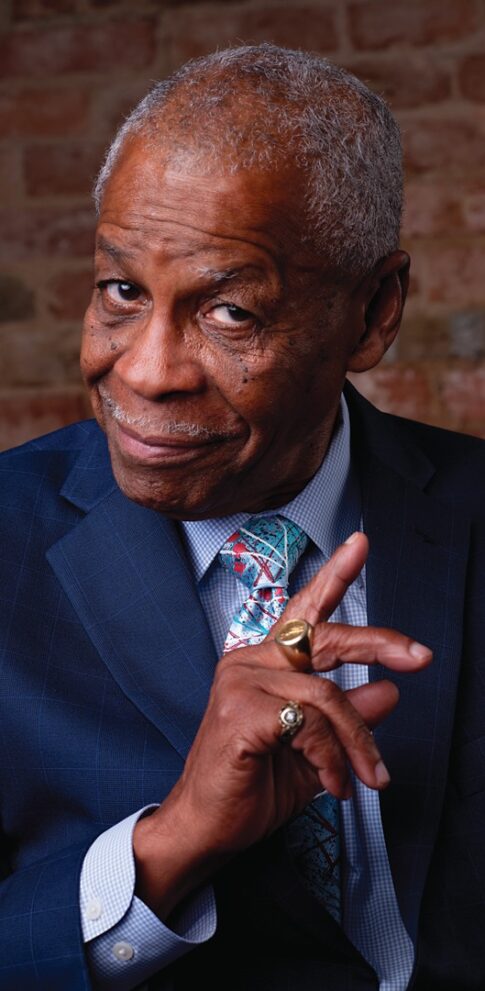

Photo Credit: Breonny Lee

BY Taylor Adams Cogan

If you really start digging into Dallas’ Black history, there’s a good chance you’ll come across Donald Payton. The Texas historian has been a contributor to the Dallas Historical Society and the Dallas Black Remembrance Project – and he’s served as a Dallas County Historical Commissioner and as president of the African American Genealogy Interest Group. He knows what he’s talking about, and he’s been doing it for decades.

It’s also easy to fall into deep conversation with Payton, who’s friendly and welcoming while being full of expertise, whether that’s from accounts of generations before him or his first-hand experience growing up in Dallas.

“Every Saturday, almost, we went down to the Central Tracks in the Deep Ellum area, that was where we did our shopping, especially for shoes and some clothes,” he says. “We weren’t just relegated to shop in Deep Ellum, but as an example talking about shoes – a lot of those guys who were in the old shoe stores, they were professional shoe repairmen and former shoe salesmen back when salesmen went from town-to-town and door-to-door. They came to Deep Ellum and set up shop.”

Payton has seemingly countless stories, fueled by his love for his own family history. His lineage goes back to 1847 in Dallas, though Payton wasn’t born here: His parents went to Cleveland for that.

“When it was time for me to be born, my mom wanted to be near her parents, and it also gave her access to integrated hospitals. Hospitals here were still segregated,” he says. “They were selective about who they treated and how they treated them.”

And about six weeks later, the family was back in Dallas, where Payton initially grew up in Oak Cliff.

“But in the ‘50s, they had housing problem in Dallas, and one of the solutions was to build Negros new housing, so they built the neighborhood Hamilton Park,” he says.

Payton grew up around neighbors who inspired the kids of his generation to go to college and become successful. That encouragement “tore down a lot of fences,” he says.

“I’m not one of those stories where we had deal with street segregation because I was around successful people: They couldn’t tell you that you couldn’t be a doctor or a lawyer because you saw them every day, and you went to school with their kids every day,” he says. “That was a good environment to grow up in. We got a little short-changed, but we didn’t have the neighborhood juke joints and neighborhood cafes – but I was exposed to them down on the Central Tracks, now what they call Deep Ellum.”

Payton spent weekends in the neighborhood, thanks to his dad who knew every “rat and rat hole” in the area. This was also where Payton was first exposed to Jewish people, hearing Yiddish and watching them run their businesses. He’d meet a variety of people creating music, finding a safe community, or just being themselves, in whatever way that meant. As much as that sounds like the Deep Ellum we know today, it was a bit different back then.

“It was fun to meet the characters down on the tracks. We had a guy named Razer Blade Ray: He ate razor blades and light bulbs: he chewed the razor blades up. He said, ‘They had me in jail, but I was eating all the lightbulbs,’” he says. “And Iron Jaw George, he could balance a table in his mouth.”

Payton’s family went to different neighborhoods throughout Dallas, frequently finding themselves in Deep Ellum.

“It was pretty integrated on the east side of Central … on the west side you had Commerce, but those were all the white stores, and you couldn’t go in if you wanted to buy something – you couldn’t try it on in the dressing room. They used to have a public bathroom downtown. You had to go in there.

“I saw the segregation, but we had everything we wanted and needed in our neighborhood.

And you had the chance to meet the guitar players,” he says. “We were able to be exposed to music and musicians and that was always cool with me, it’s where I got exposed to the blues.”

While he met musicians in Deep Ellum such as Melvin “Lil’ Son” Jackson and Andrew “Smokey” Hogg, he also found appreciation in what museums at Fair Park would offer. And endless learning should’ve been available at the Dallas Public Library.

Payton says the Dunbar library in North Dallas – the first DPL location to welcome Black residents – was so small, there were people who read every book in the space. That was until 1955, when the Central Library opened as the first racially integrated branch in Dallas.

“So when I got the chance to go downtown to the big library, and Ms. Reed used to hold the door open for me to come in and sit down, I would get some books, I would go up in the children’s department, get rolls of microfilm,” he says. “It was always kind of fascinating how the Dallas Morning News’ job was to get it first, and the Dallas [Times] Herald’s job was to get the facts. That’s why in a major city, you always had two newspapers to balance each other out. I loved reading those old newspapers and the old comic strips, that was fun for me.”

Payton says he also read the Christian Science Monitor, which he would find rolled up in his school office.

“I learned things that the Dallas Morning News and Herald wouldn’t carry,” he says. “At the time, a lot of stuff was happening in Dallas. Some things I remember – I could remember standing in line to see this young man named Tommy Lee Walker. A white woman got assaulted near Love Field, and Dallas had a fit. Somehow, this boy’s name came up.”

Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade sent the young man to the electric chair.

“I could remember all of the people standing in line to look at Tommy Lee Walker. He was kind of the Dallas version of Emmett Till,” Payton says.

Payton spent his youth also reading the Dallas Express – a publication dedicated to news of African Americans in Dallas from 1892 to 1970 (not to be confused with a contemporary website using the same name). He would later go to North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), attracted to their notable journalism program and the school that was integrating at the time.

“That was my first time ever having white teachers. There were only two boys on the basketball court,” he says. “We knew it and we felt it, but we were on the cusp of going there, to do well and make it possible for people who are going to come behind you,” he says.

He’d later watch the rise of the Black Power Movement while he was a door-to-door salesman for a Cleveland magazine crew.

“I was traveling around the country in the ‘60s. I would love to watch these people come about who were called hippies: a lot of that stuff didn’t come to Dallas,” he says. “It has been a thrill to see America change – sometimes willingly but sometimes reluctantly. To see the culture change and then to come back to Dallas and still find Deep Ellum, still find the shoeman in Deep Ellum.”

Dallas is fortunate to have Payton, and others, who openly share local history we should never forget and help fuel us to improve our city. He’s accomplished this through his various roles as an adult, continuing to be a historian and civil rights activist. Right now, he’s working on a project focused on the Dallas influence on American music. No doubt we’ll learn even more about Deep Ellum in that one.