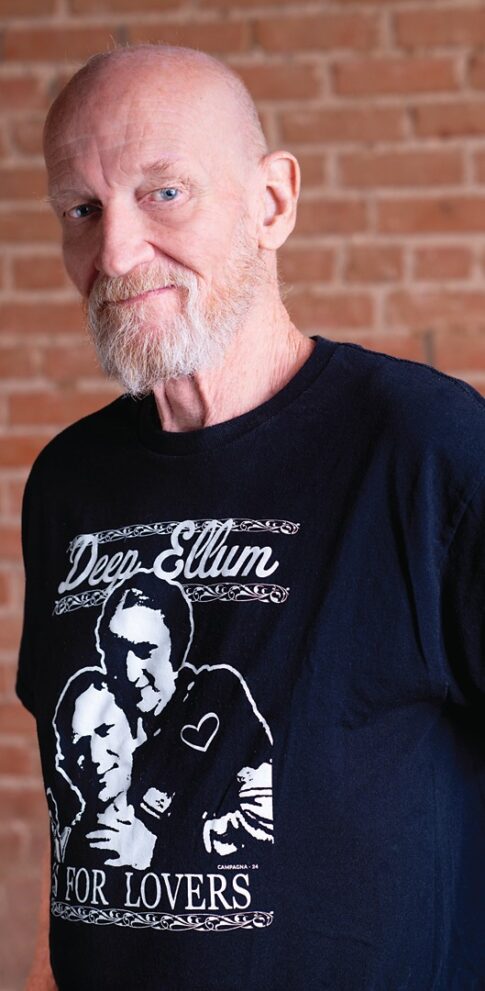

Photo Credit: Breonny Lee

BY Taylor Adams Cogan

Like a musician who dreams of playing at Three Links, a wannabe painter itches to have her work shown at Kettle Art Gallery.

It’s not just because the third Saturday of the month includes a wine walk that brings hundreds of people in to see art they might’ve never seen otherwise. It’s not even the simple but valuable fact that having art on those walls would mean they’re part of the creative system that makes this neighborhood pulse with life. It’s that the guy you passed at the entrance who was smoking a cigarette and talking to whoever wants to engage is the one who elevates local artists to a new level, one created by and for the community.

Frank Campagna started Kettle Art in 2005. And while having a 20-year brick-and-mortar business is worth celebrating, he was responsible for pushing beauty in art, music, and fun in Deep Ellum for nearly 40 years.

Known as the Godfather of Deep Ellum, there’s a strong chance you don’t need an introduction to the free-talking, whimsical character who is Frank. His name is in the corners of murals throughout the neighborhood, the gallery is a headquarters for anyone curious or experienced in art, and he’s poured his blood and sweat into the paint for years.

Frank’s family moved to Texas in 1974 by way of the Northeast US. He’d spent a brief stint in East Texas for college but made his way to Dallas.

“I was in need of quality entertainment, finding something to do at night, you go to the night clubs and all the night clubs sucked, and the bands were playing Foghat and Doobie Brothers. So, I’d go to the jazz clubs or find folk music, something that sounds original” he says.

He then made his way to Deep Ellum, specifically to a two-story building near where Cold Beer Company is today. There, he found the band the Nervebreakers, who were playing the original material he was looking for. They’d open for other bands like the Sex Pistols and Ramones, and Frank ended up creating an album cover for them.

“It was the first time I found something interesting to do. Come to find out, property was pretty cheap. I felt comfortable there because I grew up in the Northeast, with one-story, small industrial buildings,” he says.

He’d end up helping the Fly Killers, “random people I ran into,” according to the artist. They were known at the time to throw outrageous house parties, and Frank ended up booking the bands and what would become the Deep Ellum Gallery, which was right down the street from where the current Deep Ellum Community Center is.

“They were a lot of fun. And they were really strange guys. At the time, I thought, ‘I’m an artist. I want to do artwork and like booking bands, too.’ I was able to take care of my friends,” he says. “I got serious about Deep Ellum in ‘81.”

The Fly Killers did an art show to celebrate different events and show artwork, and, of course, Frank’s work was in it. He’d have a one-man show in one of the unused warehouse spaces – covering walls with black plastic and newspaper clippings with artwork in between them. It would bring nearly 300 people, “which was good for an empty neighborhood,” he says.

In 1982, Campagna ran into Dan Hitchcock at Dallas Studio Magazine – this was pre-Observer days, he’ll remind you – it was the expression magazine, which inspired Frank to publish his own.

The Dallas TV show was popular at the time, so Frank was told to find a place where anyone on earth, no matter what language they speak, could see. And that would be Main Street, Dallas, Texas, USA, he says.

“We found a spot for Studio D: 4,500 square feet on Main full of grease. It was a transmission shop beforehand and disgusting,” he says. “We grabbed a ladder and got on the roof, looked at the courtyard, and said this was it.”

The place would end up being Studio D, a perfect as a multi-space of sorts, serving as a publishing spot for the magazine, an art studio for Frank, and concerts with local musicians.

“Things were much different back then. There were only one to two clubs doing original music,” he says. “It was perfectly chaotic and I loved it. It was really ridiculous.”

Frank took over the lease and, not long afterward, was put in touch with someone who ended up mentioning the Dead Kennedys, “And I said, ‘Sure, 900 dollars sure sounds great to me and the rest is history,” he says. “I had the first nightclub in Deep Ellum even though it wasn’t a nightclub, just an empty warehouse.”

To make money for the place, they started to knock out murals in 1982; Frank would help Dan and he would do his own.

“Back then, you had to go to a shop and they say, ‘Oh, you do murals?’ Street art was not popular then. It was like pulling teeth just to tie down a wall,” he says.

The first one he did was 20 by 68 feet on Greenville, and his first in Deep Ellum was in 1980 or ‘81 — 100 by 20 feet on the side of the former Gypsy Tea Room.

“One thing I learned through the years, it doesn’t make a difference if you’re in a gallery or not, you just need visibility. And what more do you have than on a street?” he says. “It’s worth getting your name out there even though you break even in materials.”

This would later get him a regular painting gig, as he would eventually create nearly 1,000 panels promoting upcoming acts at the Gypsy Tea Room.

“It put my name on the map all of a sudden. I pushed to make the neighborhood covered in murals, not for my benefit but for everybody. I wanted it to be a mural capital, like LA, Philly. I wanted Texas’ to be Dallas,” he says.

But many people still didn’t get it – they weren’t willing to risk messing up the aesthetic of their typical brick facades. So, Frank went to the city, suggesting it designate areas for artists to compete over a four-hour period with unbiased judges determining the best. Then do the same in Austin, San Antonio, and Houston. He never heard a word.

“Here’s how you do it. You have to make it mutually beneficial for other people,” he says.

Thankfully, others did have murals in mind. In the early 1990s, Susan Reese asked Frank if he’d create murals on the Deep Ellum tunnels, but he told her he’d cost too much, and he couldn’t volunteer the time. But then, the Deep Ellum neighborhood created the association, whose first project would be the fantastic murals that would fill the tunnels.

“It popped into my head that night: Gather 30 to 50 artists and knock it out in a day. I could ask DEA [now the Deep Ellum Community Association] to take care of the city, and I’ll take care of the artists, and we got it done in a day, 6 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” he says.

Cafe Brazil bought breakfast, artists had their spots, and they were asked to take promotional material – to this day, Frank still encourages artists to put themselves out there.

At the time, he was finding himself more in visual arts but still booking bands. All the while, he was a starving artist, “not a scumbag,” he says, but one who didn’t have access to a shower and would take the opportunity if someone offered a hot meal.

“My life was hectic, but I loved it,” he says.

In 1986, he was living downtown, booking bands every week, having fun but going at full speed. When his girlfriend told him she was pregnant, he told himself it was time to grow up.

“In a lot of ways, I look at Frankie coming along, I was living in a 2,500-square-foot warehouse, all kinds of crazy bands coming through. Loudness and fun. Building next door filled with skinheads. Lots of homeless people junkies around,” he says. “June 29, 1986, Frankie gave me the perfect out, saved my life.” The last band he’d book was on that day, Sonic Youth.

He held more expected jobs – ones with more regular pay and hours but still kept his creativity driving him. His daughter, Amber, was born in 1989, and the two kids grew up going to Deep Ellum with their dad before later going down the street to attend Booker T. White High School for the Performing and Visual Arts.

He would put together Deep Ellum’s first film festival, a monthly movie night, art exhibitions, and occasionally fashion shows at the Deep Ellum Center for the Arts. They also hosted the first body art balls.

In November 2005, he’d kick off another project, a little spot on Elm Street with a courtyard in the back that would become the first location of Kettle Art. He’d go against the then-trend of closing from Thanksgiving to Valentine’s Day, insisting that rent had to be paid some way. There wasn’t much else on that side of the street at the time, just them and Deep Sushi, Frank says.

Frankie, meanwhile, started rising as a musician.

“I told him, ‘I don’t want to hear the words, ‘I want to be a rock star when I grow up,’” he says. “He never did, and he became a rock star the old-school way, playing all the time.

“Things went awry as he got older,” he says.

Frank got a call. When he was told it was about his son, he asked, “Is he dead?”

Frankie had committed suicide, shocking the neighborhood and music community, and also waking Dallas residents up to the fact that depression is real and prevalent among creatives.

“After Frankie, I realized a lot of people may think this way, I always thought some things made me look at something from both sides, question reality. With Frankie, it was, ‘OK, so now I’ve been shit on, so how do I make this good.’” he says.

He started working with the DECA crew, Pete Freedman, and Sean Fitzgerald, to put a memorial day together in seven days, just as Club Dada was about to reopen. One thousand people showed, he says. The work and funds raised led to Foundation 45, now Amplified Minds.

“That is a good way to honor somebody. I wish it wasn’t as many people doing this stupid shit, but what can you do?” he says.

His creativity keeps him going. Kettle has remained a staple in the neighborhood, aided in part by the indefatigable work of Paula Harris, whom Frank married in 2020.

Frank has previously been asked if he saw his career path as offering a viable future.

“I laughed and said, ‘F*** no, this is an art gallery,’” he says.